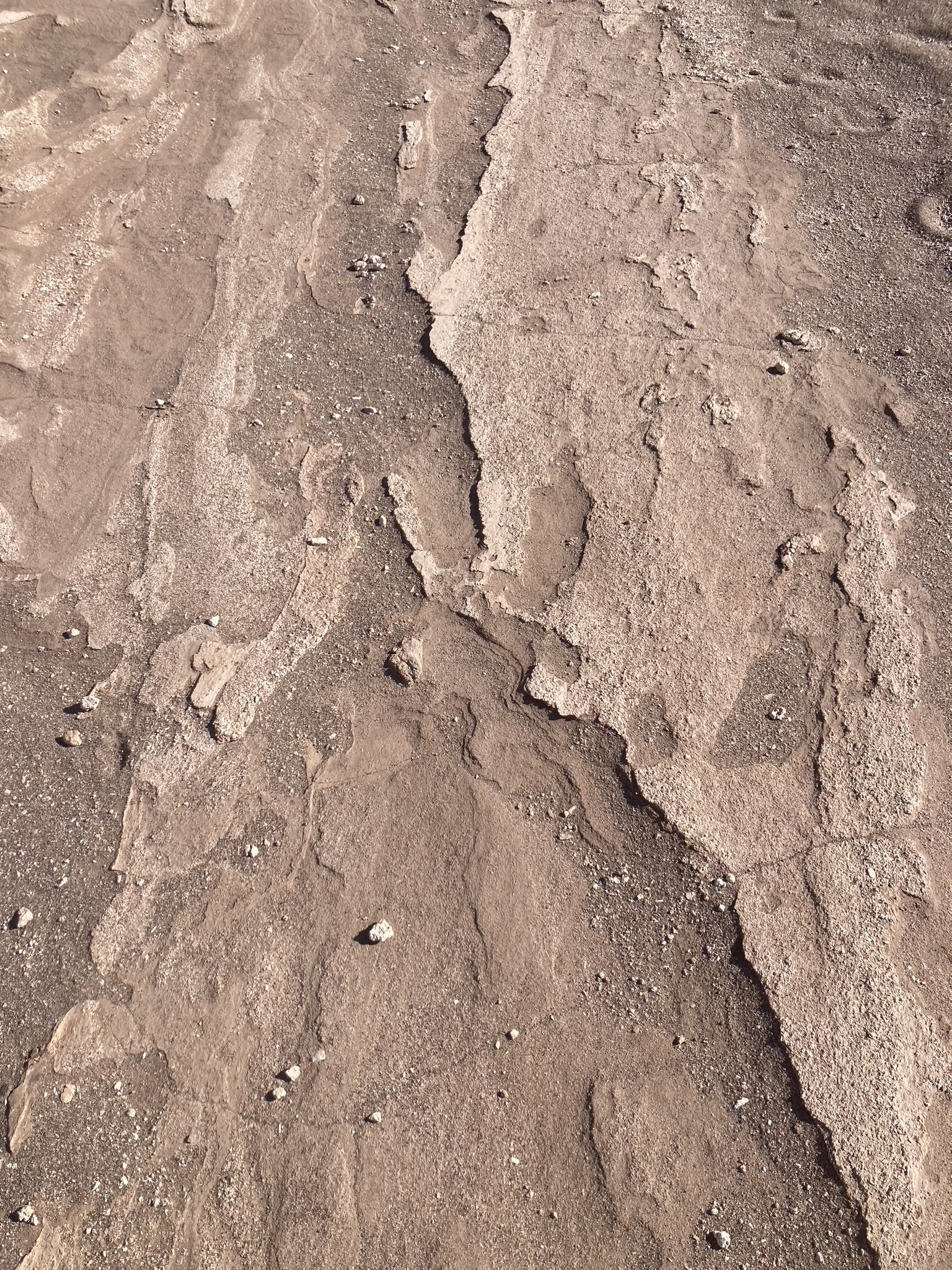

Desert1 noun1. A barren or desolate area, especially: a. A dry, often sandy region of little rainfall, extreme temperature, and sparse vegetation. b. A region of permanent cold that is largely or entirely devoid of life. c. An apparently lifeless area of water. 2. An empty or forsaken place; a wasteland:a cultural desert.3. Archaic A wild, uncultivated, and uninhabited region [Middle English, from Old French, from Late Latin desertum, from neuter past participle of deserere, to desert; see desert2PHOTO: Birds eye picture taken by Julia Flux on her arrival flight within the atacama desert, december 2023

CURRENT FUTURES unfolds through a multiplicity of meanings, revealing the deep complexity of time, space, and ecological interconnection. The term „current“ reflects both the present moment and the fluid movement of the ocean, while „future“ gestures toward the unknown, speculative possibilities.

This duality mirrors the precarious balance between the seashore and deserts worldwide where desertification and ecological degradation reshape the landscape and human and more-than-human lives.

Facing these socio-economically, environemental challenges worldwide we may have to ask ourselves:

What can we learn from deserts as well as from desertification processes?

How can we reshape our current narratives towards desirable futures?

Which language do we need to learn to reformulate these new narratives?

DESERTS AND CURRENT FUTURES -

looking at the deserts is understanding our future-

Flux research on deserts is deeply connected to the recently formed project and is a lifetime collaborative research on and within deserts and their rich cultural, mythological and ecological heritage which lead Flux to the arabic Naqab/ in hebrew Negev Desert, the Wadi Rum in Jordan, the Atacama desert in Chile, the Tabernas Desert in Spain and Poland and even unknown - the deserts of Germany.

The research aims to amplify geological voices and forces as well as the ghosts and presences of human and more-than-human migration processes shaping our past, current and future landscapes.

Desertification, seen as a process, where fertile land turns barren, serves as both a symbol of erosion and potency. This socio-ecological process is deeply interconnected with the expansion of not only natural but also artificial deserts, created and driven by agriculture, deforestation, and military activity in favor of colonization creating ghostly, hidden yet holistically influential landscapes and ultimately also human displacement.

Yet, in contrast naturally occurring deserts—though threatened—remain ecologically vital, embodying resilience and inhabited often by earthbound nomadic indigenous people reflecting the beauty and potency of adaptation and resilience.

Where desertification often is just used in reference to terrestrial processes, our oceans face globally similiar processes.

We associate with deserts remote, unreachable - yet, deserts are forming in spreading all over Europe and showing a devastating picture in Spain Andalusia, driven by agriculture.

In connection with the devastation of the outside landscapes and its effect on human lifes, migration politics, political displacement -uprooting many from their spiritual and ecological cultures - we need to ask ourselves furthermore, are we as well speaking of desertification of our inner landscapes?

The research focuses on understanding the desert not only as a physical space but as a multilayerd landscape shaped by the complex intersection of political systems, diverse ecologies and cultural and spiritual heritage . Historically, deserts have been sites of colonization, militarization and commodification, where human forces have divided, fortified, mined, extracted, militarized, polluted, and forested the land. This project aims to give a voice to the desert’s often-overlooked presences—both the human and non-human life that have lived in the desert for centuries, and the ecosystems that have shaped the land.

The desert oft seen as a barren, empty place, is actually full of vibrant, interdependent life where tensions run high: their low humidity and sparse vegetation create "electromagnetic hotspots," - like in the Atacama desert of Chile - allowing natural EM fields from lightning or geomagnetic variations to propagate with exceptional clarity. Additionally, their mineral-rich sands and rocks create telluric currents—subtle underground electric flows influenced by Earth's magnetic field and solar activity, generating localized electromagnetic fields above the surface. Within these fields human attempts to dominate the landscape interfere with natural systems and forces.

Colonization and imposed imperialism therefore has disrupted these sensitive fields and relationships, reducing the land’s, the people’s vitality and aiming to erase full existences and histories. Through Current Futures, we seek to shine light on some of these (lost) connections, asking how we can approach the desert and its inhabitants as a living, dynamic environment that is central to understanding the world’s current ecological crises.

As the global landscape shifts in response to climate change, resource depletion, and mass migration, deserts are expanding at an unprecedented rate. The World Atlas for Desertification predicts that by 2050, 90% of Earth’s land will be degraded, exacerbating problems like water scarcity, rising temperatures, and displacement. In this context, Current Futures calls for a rethinking of how we understand and connect with desert landscapes. We must move away from policies that promote isolation, extraction, and violence, and instead embrace policies that focus on care, restoration, and cooperation and reciprocity with the land.

Taking on an eco-feminist perspective, Current Futures encourages us to think of the desert not as an empty, resource-rich wasteland to be exploited, but as a space of relationality, where human and non-human lives intersect. The desert can no longer be seen as something to conquer or control; it is a space for reimagining what it means to live in harmony with nature and with each other.

By understanding the desert's histories and ecosystems, we can begin to undo the damage caused by centuries of colonization and exploitation. Current Futures calls for governance that recognizes the desert as a living, interconnected system, whose future is tied to the well-being of the planet and all who inhabit it. The project envisions a world where the desert is no longer a symbol of destruction but a place of resilience, restoration, and collaboration. Only through this shift in perspective can we hope to build a future that is equitable, sustainable, and attuned to the needs of both people and the environment.